%20(2).png) |

Congressman Matthew Lyon, Library of CongressOne of the longest sentences to explain why our ancestors |

How It Touches Genealogy Research

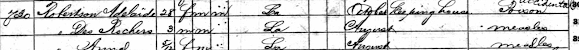

For genealogists, history’s laws don’t just shape nations, they shape the records we search. The Sedition Act may have expired in 1801, but it lives on in the traces our ancestors left behind: altered oaths, sudden moves, silenced presses, and handwritten pleas for mercy.

Every act of censorship, every trial, and every protest created documents that now lie in our archives waiting for us to uncover the stories of those who dared to speak up.

1. Immigrants Under Scrutiny

The Sedition Act was part of a package that included the Alien Acts, which lengthened the residency requirement for citizenship from 5 to 14 years. If your ancestor arrived in the 1790s or early 1800s (especially from Ireland, France, or Germany), their naturalization might have been delayed or recorded differently.

Look for:

-

Declarations of Intention and Certificates of Naturalization (1798–1808)

-

Alien Registrations and Deportation Notices in U.S. District Court Records

-

Local newspapers reporting on new oaths of allegiance

These records often list birthplaces, witnesses, and even personal statements about loyalty.

2. Printers, Editors, and Political Prisoners

|

| See Case Study Below: Congressman Matthew Lyon |

Research clues include:

-

Court dockets and indictments for “seditious libel” (especially in Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts)

-

Prisoner lists or marshals’ ledgers

-

Mentions in newspapers like Aurora General Advertiser or Gazette of the United States

The case of James Thomson Callender, a Scottish immigrant and outspoken editor jailed under the Act, is just one example of how dissenters’ names still appear in archival documents.

3. Family Migrations and Political Fear

Families linked to accused individuals often fled Federalist-leaning communities, moving westward into Kentucky, Tennessee, or the Ohio Valley.

You might find:

-

Abrupt moves between 1799 and 1802

-

Changes in occupations (editors becoming teachers, merchants, or farmers)

-

Shifts in how surnames were recorded. Sometimes they were anglicized to avoid attention

These subtle clues can lead you to untold family stories about courage and conviction.

4. Reading Between the Lines of Community Records

The Sedition Act years deepened the divide between Federalists and Jeffersonian Republicans. Local histories and petitions often reflect that tension. Your ancestor’s political leanings might surface in:

- Voting lists and tax rolls

Petitions for pardons or amnesty

-

Letters or church minutes discussing “loyalty” or “disorderly conduct”

These sources reveal not just who your ancestors were, but what they stood for.

Case Study: Congressman Matthew Lyon

The “Spitting Lyon” of Vermont and Kentucky

|

| Library of Congress: Congressman Matthew Lyon |

Matthew Lyon, an Irish-born immigrant, Revolutionary War veteran, printer, and U.S. Congressman, was one of the most famous Americans prosecuted under the Sedition Act of 1798. But, your not so ancestor may have also been prosecuted under the umbrella of this law also.

Born in County Wicklow, Ireland, Lyon arrived in Connecticut in 1764 as an indentured servant. He later settled in Fair Haven, Vermont, where he published the Scourge of Aristocracy and The Republican Magazine. In 1798, Lyon was indicted for publishing “malicious writings” against President John Adams.

His Crime

Lyon had accused Adams of “an unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and selfish avarice.” For that, he was:

-

Tried and convicted under the Sedition Act,

-

Fined $1,000, and

-

Imprisoned for four months in Vergennes, Vermont.

Genealogy and Archival Clues for Lyon

| Record Type | Repository / Link | What You’ll Find |

|---|---|---|

| Trial Records (1798) | U.S. District Court for Vermont, National Archives (Record Group 21) | Indictment, jury lists, witness statements |

| Presidential Correspondence | Founders Online (search “Matthew Lyon Sedition Act”) | Adams & Jefferson letters referencing his case |

| Newspapers (1798–1801) | Chronicling America, GenealogyBank, or Accessible Archives | Trial coverage and editorials |

| Petitions for Pardon | Library of Congress Manuscript Division | Requests to President Adams for leniency |

| Migration & Land Records | Kentucky Land Grants (KY Secretary of State) | Deeds and land patents after relocation west |

| Census Records | 1800 Vermont, 1810 Kentucky | Household listings reflecting his move |